Bottom Line Up Front

Text clustering is the application of machine learning and natural language processing (NLP) to categorize unstructured text. There are numerous applications of text clustering (for instance, identifying ‘spam’ emails). There are several approaches to text clustering, all of which include three steps:

-

Text processing

-

Text vectorizing

-

Measuring commonality or distance

Overview

The purpose of this post is to share a high-level overview of text clustering. Because this is such a big topic, this white paper is accompanied by a video demo from a “Data Talk” I once gave on this topic. This post covers:

-

Text processing

-

Text vectorizing

-

Methods for clustering

Text Processing

Text processing is the first step to any text clustering approach. In short, all of the text needs to be made ‘usable’ by reducing the words of a text document into a common syntax. Specifically, there are three steps which must occur in the text processing phase:

-

Tokenizing the text

-

Stemming the words

-

Removing the stop words

‘Tokenizing’ text means reducing all the text to lower case and splitting the entire body of text into a list of individual strings. That sounds like a lot, but its pretty straight-forward. To highlight the difference between plain text and tokenized text, here is an example of the first paragraph in Wikipedia for the term ‘Terrestrial Planet:’

Plain text (how humans read and write): ‘A terrestrial planet, telluric planet, or rocky planet is a planet that is composed primarily of silicate rocks or metals. Within the Solar System, the terrestrial planets are the inner planets closest to the Sun, i.e. Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars. The terms "terrestrial planet" and "telluric planet" are derived from Latin words for Earth (Terra and Tellus), as these planets are, in terms of structure, Earth-like. These planets are located between the Sun and the asteroid belt.’

Tokenized text (the first step in processing text): ‘['a', 'terrestrial', 'planet', 'telluric', 'planet', 'or', 'rocky', 'planet', 'is', 'a', 'planet', 'that', 'is', 'composed', 'primarily', 'of', 'silicate', 'rocks', 'or', 'metals', 'within', 'the', 'solar', 'system', 'the', 'terrestrial', 'planets', 'are', 'the', 'inner', 'planets', 'closest', 'to', 'the', 'sun', 'i.e', 'mercury', 'venus', 'earth', 'and', 'mars', 'the', 'terms', 'terrestrial', 'planet', 'and', 'telluric', 'planet', 'are', 'derived', 'from', 'latin', 'words', 'for', 'earth', 'terra', 'and', 'tellus', 'as', 'these', 'planets', 'are', 'in', 'terms', 'of', 'structure', 'earth-like', 'these', 'planets', 'are', 'located', 'between', 'the', 'sun', 'and', 'the', 'asteroid', 'belt’]’

The second step in text processing is stemming the words. This too is fairly straight forward (thanks to the hard work of data scientists over the past decade). Stemming words just means reducing them to their root word (usually in latin). To highlight the difference between tokezined text and tokenized + stemmed text, lets revisit the example text from above:

Stemmed text (the second step in processing text): ‘['a', 'terrestri', 'planet', 'tellur', 'planet', 'or', 'rocki', 'planet', 'is', 'a', 'planet', 'that', 'is', 'compos', 'primarili', 'of', 'silic', 'rock', 'or', 'metal', 'within', 'the', 'solar', 'system', 'the', 'terrestri', 'planet', 'are', 'the', 'inner', 'planet', 'closest', 'to', 'the', 'sun', 'i.e', 'mercuri', 'venus', 'earth', 'and', 'mar', 'the', 'term', 'terrestri', 'planet', 'and', 'tellur', 'planet', 'are', 'deriv', 'from', 'latin', 'word', 'for', 'earth', 'terra', 'and', 'tellus', 'as', 'these', 'planet', 'are', 'in', 'term', 'of', 'structur', 'earth-lik', 'these', 'planet', 'are', 'locat', 'between', 'the', 'sun', 'and', 'the', 'asteroid', 'belt’]’

The final step in text processing is removing stop words. The easiest way to think of stop words is to consider words that you would not start in upper case in a title. For example, ‘a,’ ‘the,’ and ‘an’ are all examples of stop words. Removing stop words, like the first two steps, is not difficult. Thankfully, some great developers created a library called NLTK which already has a huge list of stop words in dozens of languages. By using the NLTK library, one can remove stop words from text in just a few short lines of code. (Thank you NLTK!). Here is what the above text looks like when the stop words are removed. Note: this text is the final, processed text, meaning it is ready for text clustering!

Text without stop words: ‘['terrestri', 'planet', 'tellur', 'planet', 'rocki', 'planet', 'planet', 'compos', 'primarili', 'silic', 'rock', 'metal', 'within', 'solar', 'system', 'terrestri', 'planet', 'inner', 'planet', 'closest', 'sun', 'i.e', 'mercuri', 'venus', 'earth', 'mar', 'term', 'terrestri', 'planet', 'tellur', 'planet', 'deriv', 'latin', 'word', 'earth', 'terra', 'tellus', 'planet', 'term', 'structur', 'earth-lik', 'planet', 'locat', 'sun', 'asteroid', 'belt']’

Text Vectorizing

Once all of the text has been tokenized and stemmed, and the stop words have been removed, the next step is to turn the text into numbers. This is called ‘vectorizing’ the text. Vectorizing text is a big topic. Some of the brightest developers, engineers, mathematicians alive today have dedicated themselves to solving this issue. As a result of their hard work, there are numerous methods available for vectoring text, to include:

-

Frequency (counts word frequencies)

-

One-Hot Encoding (binarizes term occurrence as 0 or 1)

-

TD-IDF (normalizes term frequencies across documents)

-

Distributed Representations (context-based, continuous term similarity encoding)

The frequency method is the easiest to explain, and will therefore be the example used in this post. Please note that I give more in-depth examples of other methods in the Data Talk, which I'm aslo happy to provide on request.

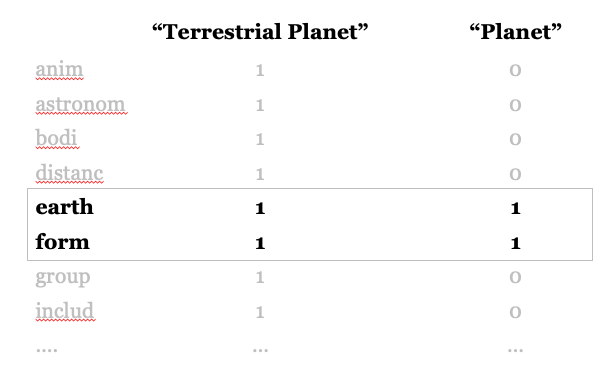

The frequency method of text vectorizing works by simply creating a matrix of each of the words between two text documents. This matrix is populated with the frequency of each of the words in the text documents. For example, imagine we wanted to make a frequency matrix among the processed text from the Wikipedia entries on the terms ‘Terrestrial Planet’ and ‘Planet.’ The matrix would be derived from a table with three column. In the first column, we would list every single word contained in either, or both, of the text documents. In the second column, we would list the word frequencies for each of the words in the first column for the term ‘Terrestrial Planet.’ The third column would be the same, but for the term ‘Planet.’ The matrix would look something like this:

Text Clustering

The final step in text clustering is to group the processed, vectorized text documents. Like previous steps, there are several approaches for doing this. The three most common approaches are:

-

Jaccard Similarity

-

Cosine Similarity

-

Euclidean Distance

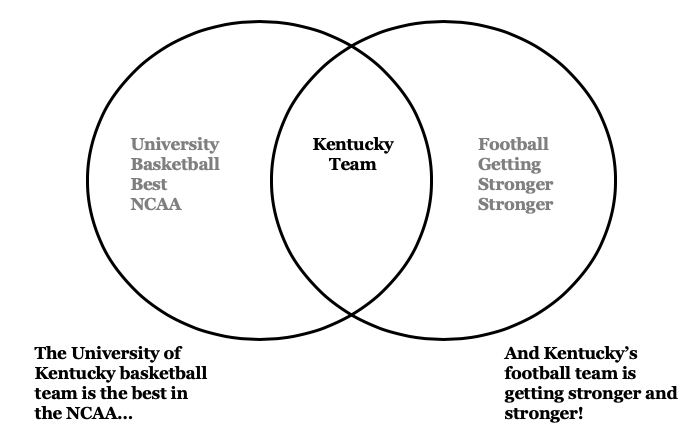

The Jaccard Similarity method is the size of the intersection of two text documents divided by the size of the union for both sets of text. This is a relatively easy method to understand and implement, so it is usually the first stop for text clustering projects, even if the developers ultimately intend to use a more sophisticated method. The below graphic helps visualize this concept:

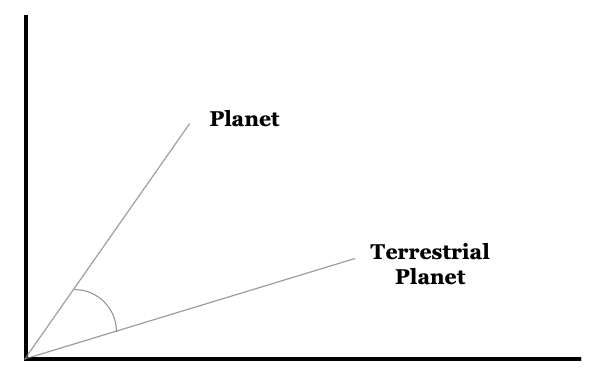

The Cosine Similarity method plots text objects and measures the angle between them. The idea here is that objects with closer cosines are more similar. This is useful because it helps identify documents with similar text, as opposed to documents with the exact same text (like the Jaccard Similarity). The below graphic helps visualize this concept:

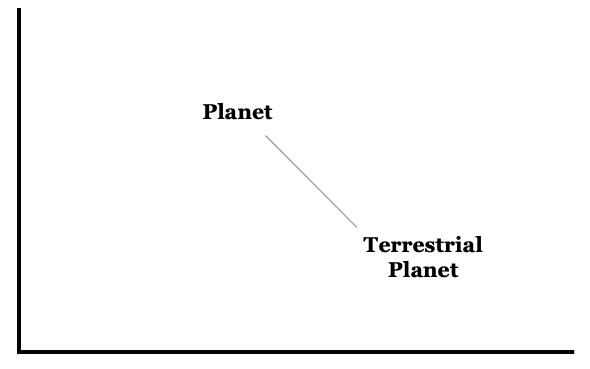

The Euclidean Distance method plots objects, similar to the cosine distance method, and measures the distance between them. The below graphic helps visualize this concept:

Summary

There are several methods for text clustering. The main idea behind all of the them is to transform the text into vectors (a matrix of numbers) and then to measure the distance between those numbers. Before doing so, however, the text documents must be prepped for vectorization. All the common “stop words” (e.g. “a,” “an,” “the”) are first removed from a text document. Then each of the words are reduced to lower case and “stemmed,” meaning they are reduced to a common form. Consider, for instance, the following sentence: “There are millions of dogs in New York City.” Once prepped, it would be reduced to: “million,” “dog,” “new,” “york,” “city.”

Despite the seemingly endless number of blogs about the best methods for text clustering, there is no “best” for text clustering. The best approaches depend heavily on the situation for which the text clustering will be used. For instance, clustering text on twitter (which has heavy use of slang) requires a vastly different approach than clustering legal or business text (which will repeat the use of words which have closely defined and well understood meanings).